\\

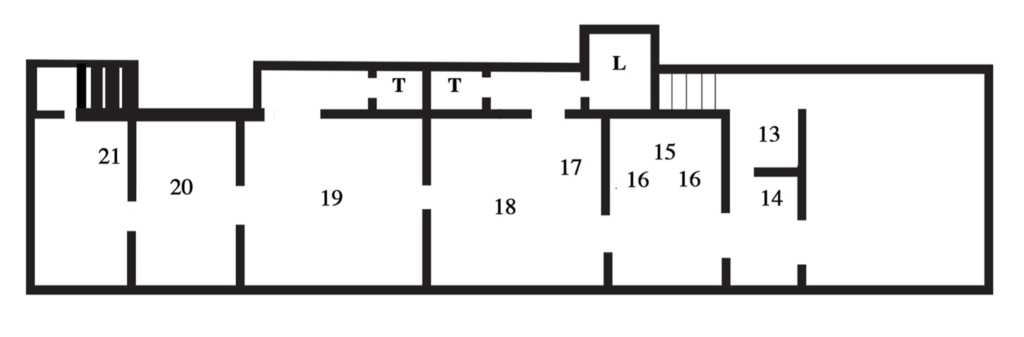

13. Keren Cytter (1977, Jaffa, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel)

The Victim, 2006 is a film shot within a domestic setting in which the events of five unnamed characters unfold around two basic narrative cores: a woman’s choice between her lover and her son (played by the same actor) and the preparation of a cake.

Soon, it is clear that the film’s characters are nothing more than voices in a script and their dialogues an uncovering of the narrative functions of the film medium. Indeed, language occupies a central role in Keren Cytter’s work, played most often enigmatically and aimed at an existential reflection on reality.

Keren Cytter uses video — making use of rather simple handheld instrumentation, such as the handycam, and rendered low-fi — writing, graphics, and performance to reflect on the use of expressive artifice in the construction of language and the tension between reality and fiction. His filmic work, inspired by the Nouvelle Vague and the Dogma movement, investigates how an individual’s social background affects his or her psychology and interiority, exploring a sense of chaos that uproots and deconstructs linear thinking or the order imposed on reality, as a reflection of the ‘inscrutability of reality itself.

Similarly, its characters, as in the case of The Victim, find themselves on eternally repeated dead-end streets of plots without resolution that undermine the unity of place, time and history, alternating focus between language and behavior.

The film, placed in dialogue with the works of Lorenzo Scotto di Luzio, the sculptures of Piero Golia and Eva Rothschild, then the installation of John Bock, shares with the works of these artists a degree of transparency that questions not only reality but also the boundary between artistic categories and the linearity of Western thought.

13. Keren Cytter, The Victim, 2006, Screening installation, colour, sound, 5’ continuous loop

14. Jonathan Monk (1969, Leicester, UK)

A Work in Progress (to be completed when the time comes) 1969 -, 2005 is a black granite funerary sculpture that the collector is called upon to finish when the time comes, mocking the procedures, system and workings of the artwork in a play of parts between artist and work owner.

Often appropriating and deviating slightly from the works and ideas of conceptual, minimalist, and post-minimalist artists, Jonathan Monk’s work destabilizes the principle of uniqueness, working through meta-artistic operations, questioning authorship, and desacralizing the myth of the artist-genius.

Monk’s practice ranges across different media and formats, from neon and painting to books, sculpture and photography, video and installation. Elements of the “stories” that construct his works are drawn from and mixed with autobiographical events, historical references or overlooked aspects of everyday life. Members of Monk’s family, artist-myths from previous generations or perfect strangers, as well as everyday objects and images, enter the work without hierarchical distinctions or boundaries between high culture and ordinary existence.

By questioning the status of originality, of the author and thus of the artwork itself, of the art system and its rules or conventions, Jonathan Monk’s works often reflect potentially infinite ways of interpreting history, art history or facts, revealing the innumerable potentialities of reality.

14. Jonathan Monk, Sometimes I ask myself why then I remember it isn’t my problem, 1997, watercolour on paper, 25 x 35 cm

15-16. Lorenzo Scotto di Luzio (1972, Pozzuoli, Italy)

Atti di Panico, 2000 is a photographic series of six self-portraits corresponding to six different poses and expressions that pathetically summarize the artist’s condition.

While many of the artists’ gaze rests on their surroundings, social constructs, art history, historical past and political present, Scotto Di Luzio’s practice introspectively addresses the anxieties, pressures, and pretensions placed on the figure of the artist, uncovering with awkward irony the nerves under the skin of the art system, stepping in and out of his own and other roles, as happens in the photographic series of cross-dressing works (Confezioni Taylor, 2000, o Lorenzo Scotto di Luzio interpreta Luigi Tenco, 2002), in which the artist is both wearer and songwriter.

Big Mama (2003) is a 1950s display cabinet more than common in Italian homes. As the viewer passes by, the glassware wobbles, simulating an earthquake tremor. In accordance with an irony now more commonly referred to as cringe, not liberating but chilling, which pins us down in a feeling of disarming hilarity, Big Mama is one of Scotto Di Luzio’s desiring machines inspired by the experience so common to those born between the 1960s in Campania of the earthquake. The tremor of the quake spreads like a chill in the memory of those who have memories of that period and the constant tension that accompanied the experience.

The works in Scotto Di Luzio’s exhibition project a view from within the art system, but acting on multiple levels. The act of panic is not only the panic of the artist, a self-referenced monument to his personal condition in the art system. But a form of panic and asphyxiation toward the dominant culture, the impossibility of emerging under the crushing weight of the most intransigent ideological aspects that contemporary society imposes: cancel culture, populism, social denunciation, a new puritanism that everyone seeks in the work and its role. Thus Big Mama is also a celebration of a seemingly conservative culture, which in a historical moment of avant-garde and progressivism at all costs, becomes the only possible form of subversion: grandmother’s glassware is the antidote to tokenism.

15. Lorenzo Scotto di Luzio, Big Mama (02), 2004, Cupboard, photosensors, electric engines, party favours, 220 x 240 x 40 cm

16. Lorenzo Scotto di Luzio, Atti di Panico, 2000, 6 Digital prints on photographic paper, 100 x 70 cm (each)

17. Eva Rothschild (1971, Dublin, Ireland)

Sit In, 2003 is a plexiglass sculpture centered on the interlocking of different geometric shapes, vertical sections of three different triangles and the repeated circle motif within these elements with an almost drawing-like levity.

Eva Rothschild’s work is centered around a reflection on the familiarity of geometric shapes, their interconnected arrangement in space, and the way the viewer looks at and experiences these elements.

Moving from an artistic reflection connected to the history of postwar sculpture, from Anthony Caro to the minimalism of Richard Serra, the post-minimal sculpture of Eva Hesse, or the work of Isa Genzken, Rothschild’s works are continually strained between form and narrative, geometric configuration and organic sense.

Eva Rothschild’s practice has indeed been called one of “messy” or “magic” minimalism, insofar as, although what we see is what it is, pure geometry and physical forms in space, the artist seeks to investigate how these objects are invested with a power beyond their materiality. In this, the tension between industrial finiteness, tactile sense and the handcrafted quality of their appearance also plays a central role. The role assumed by color is also fundamental, almost never mixed with others, almost always pure and monochrome, as are the materials — which range from plexiglass, to jesmonite — then the titles, which constitute the final piece that completes Rothschild’s works.

In fact, the works play with a sense of precariousness and incompleteness, totally presentified in their presence in space, which, if on the one hand is the “magic” figure, on the other hand matches the misleading indications of the titles. In this, Eva Rothschild’s sculpture holds a narrative quality inherent in the forms and materials that breaks with formal completeness and insinuates a layer of doubt and estrangement in the viewer’s vision, in dialogue with the narrative creation of Piero Golia’s work.

17. Eva Rothschild, Sit in, 2003, Black plexiglass, 260 x 120 cm

18. Piero Golia (1974, Naples, Italy)

Located on the second floor of the Fondazione Morra Greco, Untitled (Carpet), 2003 by Piero Golia is a sculpture that catalyzes the space around it. The arrow made in spray on the surface of the carpet functions like the needle of a compass that always points toward the artist’s home: a contrived arrangement for the sculpture to orient its surroundings with its own presence.

The carpet, as such, achieves a mostly decorative function within the domestic atmosphere. The sculpture, with its horizontal flatness and textile decoration, plays with a pictorial sense, but triggering a short circuit. Untitled (Carpet) catalyzes the arrangement and energy around it by reflecting on the conceptual power of the symbol, demystifying the boundary between painting and sculpture and pushing toward pure contingency the character of the work, which, in this way, becomes transversely site-specific for any environment.

In dialogue with Eva Rothschild’s work, both sculptures make use according to different strategies of storytelling and linguistic reflection on the medium that in Goliath’s practice completely deny the boundary between painting, sculpture and behavior, as well as between art and life. The carpet, an extension of the artist’s home, becomes the connector between the personal subjective dimension and the collaborative communal dimension of art.

From the co-founding with Eric Wesley of the Mountain School of Art, the opening of a super-inclusive club such as the Hollywood Chalet designed with architect Edwin Chan, or Luminous Sphere, 2010, the intermittently luminous globe on the roof of a Los Angeles hotel that lights up when the artist is in town, there seems to be a continuous osmosis between autobiographical anecdote and public works, mythology of the self and the creation of a community around art: the poles through which Piero Golia’s actions, sculptures, paintings, choreographed directions of random events or multi-act exhibition epics swing.

18. Piero Golia, Untitled (Carpet), 2003, Carpet and spray paint, 200 x 140 cm

19. John Bock (1965, Amt Schenefeld, Germany)

Erdmann, 2002 is a film made in tandem with John Bock’s performance presented at Documenta 11 in 2002 in Kassel.

Literally “man of the earth,” in Erdmann the artist emerges from the depths of the earth after a gut catabasis inside below a hut presented in the Abteiberg Sculpture Garden, where the artist engages in a theater of adventures and dialogues with sculpture characters made of wood, fabric, and found objects with organic features that inhabit the bowels of this setting. Equipped with a hand-held camera projected live outside, the audience follows the scene live as if in an endoscopy.

Bock re-emerges from this underground adventure by passing through a claustrophobic underground tunnel that connects the hut to the skeleton of a car.

John Bock defines many of his works as Summenmutationen, or sum and mutations, like most of his action-lectures, or film-performances that most often feature the artist, actors, and the audience intent on interacting with a group of character-sculptures within amateur environments constructed from debris, vehicle wrecks, and found materials.

In a mix of German, English, and French, John Bock’s performances are conceived as a parody of academia and traditional teaching methodologies, in which the viewer is directly engaged.

John Bock’s work investigates the primitive drives of human beings, such as drinking, eating or organic waste, striking at the shadowy, schizophrenic and repressed side of the Western psyche, bringing to the surface psychological and social taboos repressed in the everyday. His Summenmutationen see the interdependence between objects, actors, film, and, of course, the viewers, who are called upon to have a total experience of art, to be immersed and almost “loose” in the enjoyment of the work.

The repurposing of the installation, conceived by John Bock specifically for Keep on Movin’, disrupts the rationalism that substantiates the basis of thought and language, pitting the cultural history of ideas and the normativity of neoliberal society against an anti-history and anti-language.

19. John Bock, Erdmann 2002, mixed media installation on shelf, DVD, variable dimensions

20. Cathy Wilkes (1966, Belfast, United Kingdom)

Most Women Never Experience, 2005, is an environmental installation by Cathy Wilkes in which objects drawn from everyday life and assembled in narrative form, with their simple presence charged with emotional and social meanings, describe an existential condition and a form of political representation. In this case, elements drawn from the domestic sphere of the middle class, such as televisions or a broken crystal glass, alongside others that evoke motherhood, such as the stroller, allude to the presence-absence of themes related to the world of women and care, which in so doing reveal the symbolic potential of these objects.

Cathy Wilkes’ surreal compositions invite the viewer to follow the meanings and associations evoked by material culture, investigating the politics of representation of the body and of women, shedding light on the signs, stereotypes, and objectification most often projected by a male gaze on the female figure. In this sense, icons related to the domestic sphere, motherhood, or the mannequin, are symbolic signs of this typification that instead of being demonized by the artist are bent to a form of meta-functioning that reveals the power at work in the gaze. The body-mannequin or object-fetish becomes a semantic space of social and political meanings.

Cathy Wilkes’ work thus attempts not only to explore the politics of bodies and the feminine, but above all to patch up the unbridgeable gap between interiority and the experience of the external world.

In dialogue with the work of Kai Althoff, to whom Wilkes’s work has also been juxtaposed during the 1990s, and with John Bock’s installation, this triptych of artists and respective works narrate the condition and influence of society on the individual, the subjective and emotional sphere, thus the way in which iconography, but also objects of material culture can be ways to penetrate reality but also inevitable obstacles that settle in individual memory and unconscious, where society continues to exert its forms of power.

20. Cathy Wilkes, Most Women Never Experience, 2005, Paintings, television sets, sink, metal constructions, pram, other variable parts, variable dimensions

21. Kai Althoff (1966, Cologne, Germany)

Palmsonntag, 2002 depicts Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, which in the Catholic calendar of Christian tradition coincides with the celebration of Palm Sunday. The holiday precedes the celebration of Easter, thus the death and resurrection of the Son of God, by one week. According to the New Testament, Jesus is said to have entered Jerusalem on the back of a donkey, hailed by the crowds who flocked in greeting waving palm branches and spreading cloaks across his path.

Kai Althoff works with painting, photography, performance, video, music, installation and poetry. Palmsonntag is part of a series of twenty-three paintings made for the artist’s exhibition at the Diözesanmuseum Freising (with Abel Auer) in 2003, a Catholic museum. All the works from the series, including the one on display, are canvases mounted on a double frame fixed by a layer of boat paint, on which the artist paints using a variety of techniques, with watercolors, varnish, fabric paint, and collage.

Her painterly work is characterized by a mixture of iconographic references, from fashion history to art history, from references to Nordic Christian Catholicism or German Renaissance, to postwar German expressionism. Ancient and modern history mingle with folklore and religion, as is the case in Palmsonntag, where Althoff’s Christ is greeted by a crowd dressed in contemporary garb: officiating bishops, monks and cardinals, down to a man in tailcoats painted against an abstract background that recalls in composition the early Nabis and Symbolist atmospheres of post impressionism, with which the work shares the theme of the sacred and vision.

Not only the artistic practice but also the personality of Kai Althoff in the contemporary art system, reluctant to the professionalism of the artist, testify to the historical expression of a generation that deliberately chooses not to participate in the hustle and bustle of today’s neoliberal society, remaining on the margins of the work, just as in his work it is the biographical element and experience, absorbed and imprinted unconsciously by historical time, of one’s childhood, or origin, that resurfaces in a mysterious manner elusive to definitions.

21. Kai Althoff, Palmsonntag, 2002, Boat lacquer, paper on canvas, watercolour, varnish, 70 x 90 x 4.5 cm