\\

1-2. Július Koller (1939 Piešťany, Slovakia – 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia)

The works Universal Physical-Culture Operation (Attack) (U.F.O.) and Universal Physical-Culture Operation (Defensive) (U.F.O.), both from 1970, are two black-and-white photographs taken by his collaborator and partner in life, Květoslava Fulierová, like the majority of portraits from U.F.O.-naut J.K., Anti-happenings and other operations conducted from 1970 until 2007, the year of his passing, by Julius Koller.

Koller’s Universal Physical-Cultural Operations alludes to the centrality of sport in the artist’s life, which becomes an example of freedom and emancipation, as it is ordered according to well-defined rules, fair-play, and civic example. Likewise, the play on words with the acronym U.F.O. (declined from time to time according to always different neologisms and associations), connects to the fascination with the cosmos and science fiction, common to the generation that grew up witnessing the first trips to the moon. All aspects that contribute to the creation of “cultural situations,” set and addressed in the present but for the memory of posterity.

In the aftermath of the Prague Spring and the failed attempt to establish a “socialism with a human face” in 1968, following the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops and the suppression of any reformist thrust, from 1970 Czechoslovakia experiences a phase of “normalization” aimed at restoring an orthodox communism that will crush any freedom of expression, information, and art that does not conform to the regime for some 20 years onward.

Julius Koller introduced the concept of Universal Futurological Cultural Operation, or U.F.O., in 1970 as an existential manifesto marked by the creation of a new reality through cultural situations so grafted into existence that they could not be called art — or be recognizable.

The juxtaposition of Julius Koller’s work with conceptual art is an easy temptation that betrays the monopoly of the Western canon in the genealogies of art history as a normative paradigm incapable of taking into account the differences, nuances and identities external to North American and European art. Koller’s art is not behavioral art, aesthetic or conceptual reflection, or even anti-art in line with the neo-avant-gardes, but non-art.

In fact, the historical and political context in which Julius Koller’s artistic and life parable is set is fundamental, though not unique, to understanding his theoretical rather than artistic positioning, his cynical look at absolute truths, museification and art itself, which invites us to look at a refounding of art and its institutions as an ethical and existential choice, of almost civil awareness together.

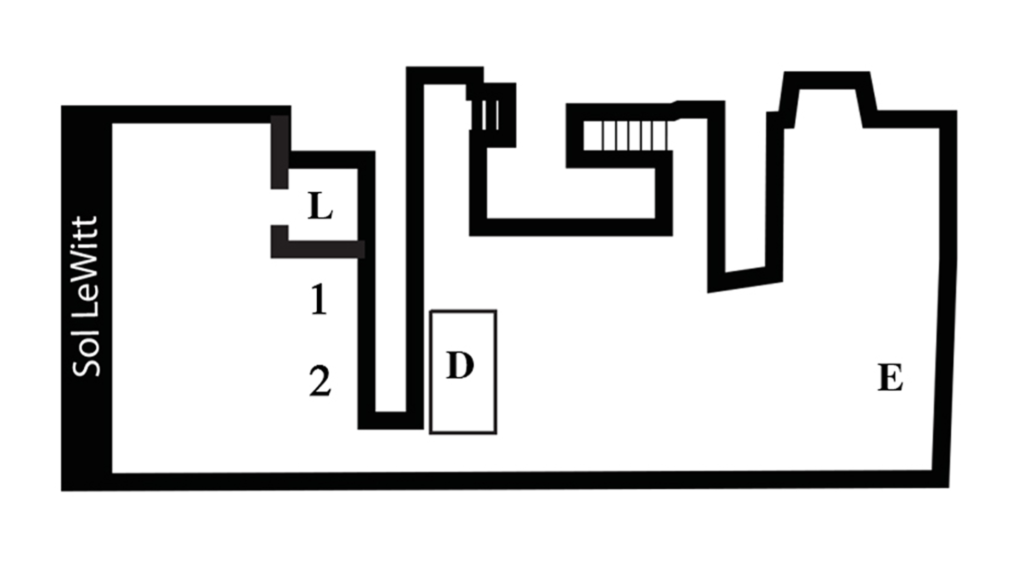

The dialogue between Julius Koller’s U.F.O. operations and Sol Lewitt’s Wall Drawing is a prism through which to view the exhibition, symbolically reflecting the impossibility of an absolute point of view on things that can fully exhaust their meaning, along with the need to continually question our point of view and that of the systems in society in order to come as close as possible to embracing the complex multiplicity of the real.

1. Július Koller, Universal Physical-Culture Operation (Defence) (U.F.O.), 1970, B/W vintage photograph, 34 x 25.5 cm

2. Július Koller, Universal Physical-Culture Operation (Attack) (U.F.O.), 1970, B/w vintage photograph, 24.5 x 17.8 cm

3. Cezary Bodzianowski (1968, Szczecin, Poland)

Casio Pay, 2010 is a double video installation by Polish artist Cezary Bodzianowsky that plays with time and space.

In the English language, lost time is called “Borrowed Time.” But borrowed from whom, or lost to what? If it is society that imposes on us a rhythm, that of production and work, which in fact has nothing to do with our human nature or natural time, but which every time we transgress is “lost” or borrowed, then, by losing time, we are reclaiming something of our own.

Acting as an outsider, Cezary Bodzianowki’s “occurrences” insert an element of absurdity into the course of everyday life, subtracting from the concatenations of meaning, but also from the norms and codes of behavior imposed by society, any legitimacy with actions of disorienting nonsense that contribute to desacralizing the gesture of the artist-genius.

Trained at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts in a climate of experimental performance theater, Cezary Bodzianowski works primarily with video, performance and image, in collaboration with his partner, Monika Chojinicka, who films and captures his actions in front of the camera.

Having moved to Belgium in the mid-1990s, Bodzianowski’s work transcends into surrealism by placing himself in the wake of the legacy of Nagé, Magritte, and Broodthaers later, transferring into his works a sarcastic sense of absurdity, irony, and isolation, as a cog in a system, the social or artistic one, out of place, malfunctioning. Except that all such systems seem to be hopelessly ill.

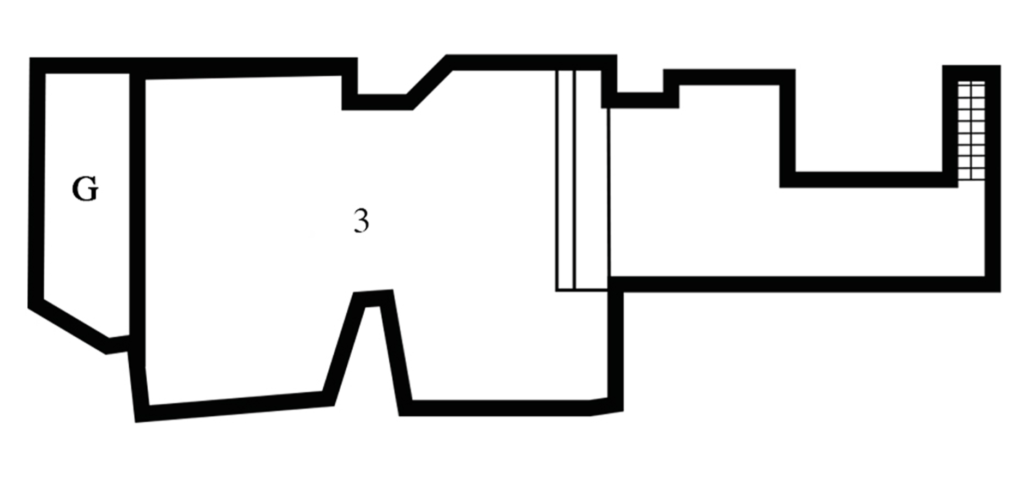

3. Cezary Bodzianowski, Casio Pay 2010, Double video installation, monitor, projection, variable dimensions