03.03.2012 \\ 18.05.2012

Ryan Gander’s works take their origin from a research process, a development that always appears fragmented, unfolding like a series of smoke screens, that lead the viewer into unexpected detours. One of the characteristics of his practice is to create artworks that take every possible form, from sculpture, photography and painting to installation, sound and film, slideshows, objects and books, but also lectures and other entirely new forms—like the invention of a fictional word that he tries to pass into our everyday language. Ryan Gander likes to surprise and unsettle his audience.

While his works remain firmly connected to a conceptual logic, they provide snippets of lived experience, referring to various fields of knowledge, clichés, art history, the art world, and, most recently, to the modes of appearance and mediation of art itself (the places of art, exhibitions and their corollaries, but also their reception in the press).

The experience of art — from frustration to inaccessibility — and the impossibility of its transcription was the core of Gander’s project Locked Room Scenario for Artangel in London. The spectator was pushed into the role of a detective, approaching the works as traces and evidence, scrutinizing over material details and imagining those that couldn’t be perceived, a scenario which ultimately led to a troubling feeling of confusion.

Lost in my own recursive narrative is the artist’s attempt to investigate the role of a creator when he himself becomes both the director and the subject in the production of the work. This exhibition marks an interesting transition for Gander, who is frequently critical of artists who appear within their own work, and is perhaps his most autobiographical show to date.

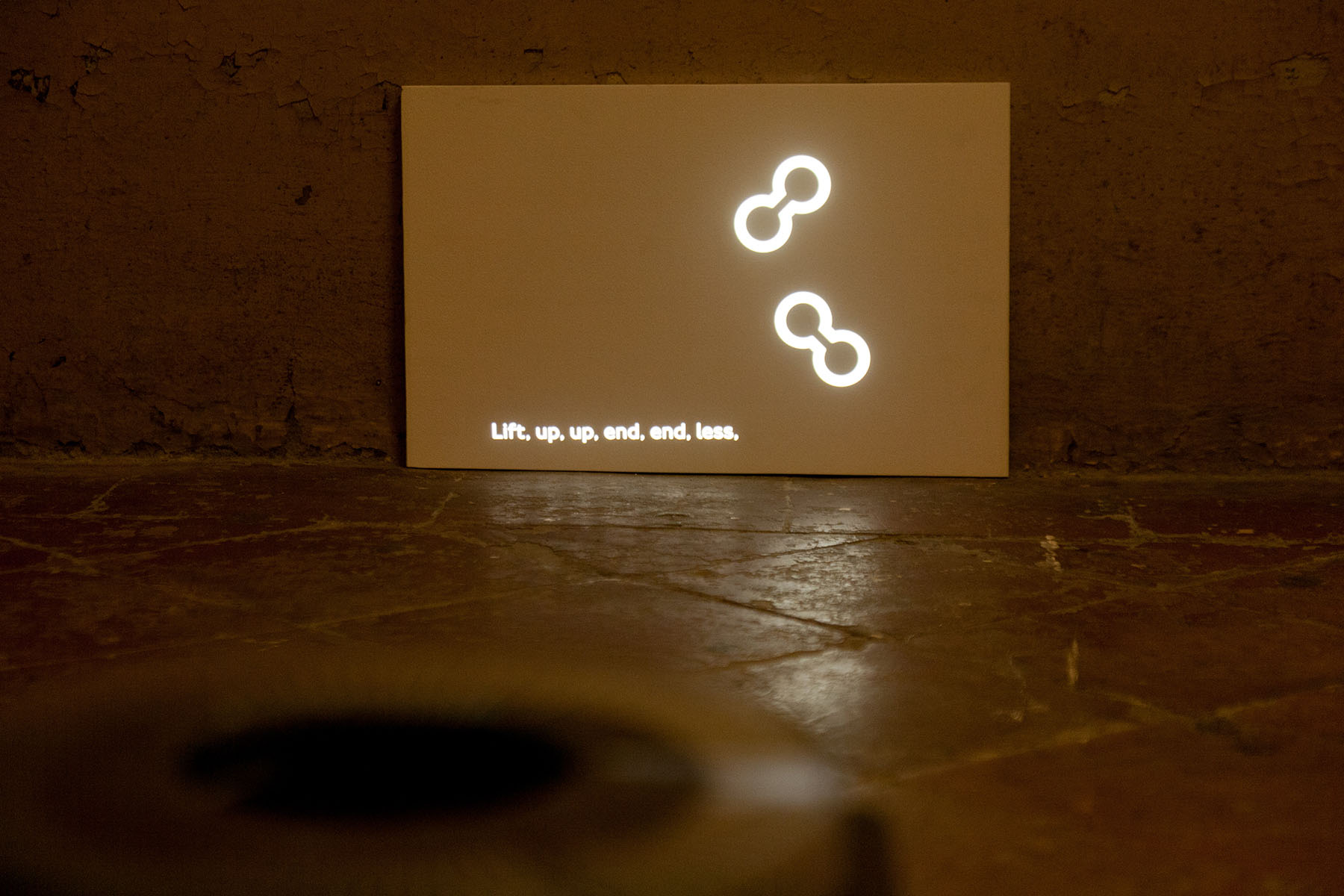

Placed just at the entrance, the work attached to the ceiling is A Sad Deceit, 2011 which takes the form of a tiny and fragile mobile made from the elements of the Didactease emblem which uses mathematical symbols to produce the sentence “There exists only one definition for everything, everywhere at any one time”. This introduction serves as a constant reminder that there’s never “one definition for everything, anywhere, at any one time”.

In a vitrine, Investigation #39 – Already aware of its own helplessness, 2009 is a tiny badge rendered in solid silver representing a hybrid of the Ferrari and Peugeot logos. This collision of forms is emblematic of Gander’s work.

Human’s being human (blue on yellow), 2012 takes the form of an advertising billboard. A young French fashion model dressed in blue is standing within the space of the gb agency, surprised by a photographer as she gazes at a painting that consists of a yellow circle on white canvas. But here, the model is not posing, her accusing gaze is directed to the photographer but also to the spectator. Using the codes of the advertising imagery and integrating them into the context of art and its exhibition, Ryan Gander seems to question the intimate relation to the artwork and the fragility of this link.

The lady’s not for turning – (Alchemy Box No. 32), 2012 is part of the series of Alchemy Box, which experiments with the audience’s trust and belief: the boxes are sealed and contain some objects, which are revealed to the audience in a list displayed on a nearby wall. The only way to know if the objects are really in the box is to open, and thereby destroy the box. What is more important? The ideas in the box, the recipe and ingredients for a new work that doesn’t yet exist, or the box that contains them, which appears to be a sculpture and is considered art? This Alchemy Box takes the form of two platforms, one circular and one square, that we might expect to find in a drawing studio and on which the model may pose. The elements listed on the wall include objects relating to the themes of reconstruction, documentation, as well as the mediated experience. For example, one can read the description of a color photograph taken during the artist’s research, an image leading to the production of the work Tell my mother not to worry (I), also present in the exhibition.

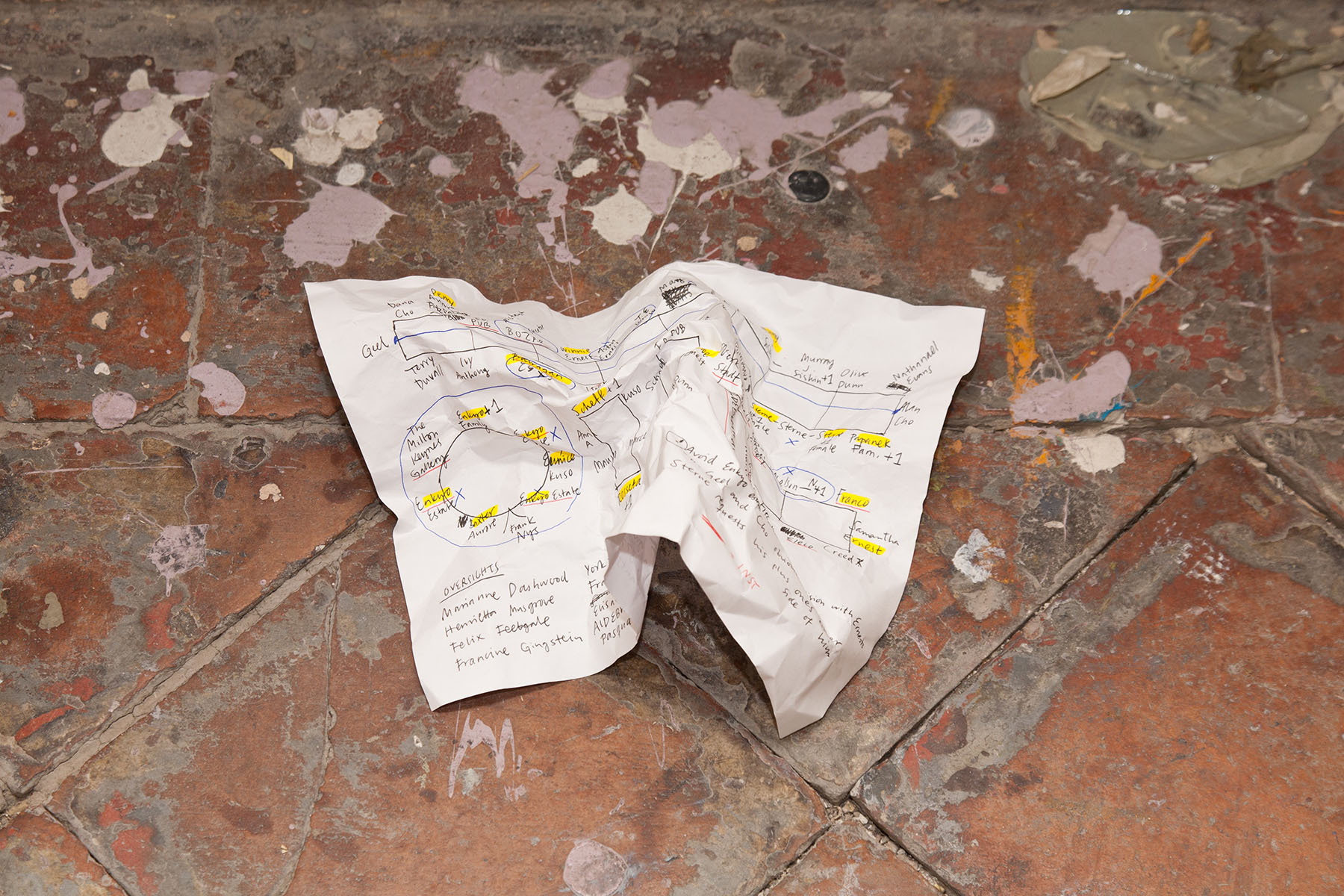

A diagram crumpled up and abandoned on the floor, titled Career seeking missile, 2011 which seems apparently hand written, shows a dinner seating plan. The spectator may pick it up, ponder over it and take it away. The paper has been printed in coloured ink so that it appears to be a unique set of notes, introducing a confusion in its status. Each time the diagram is taken it has to be replaced with another crumpled up sheet so that it always appears on the floor. While studying it carefully, one understands that the sheet gives clues to the hierarchy of some artists and invited guests at an opening dinner, while the notes explain the relationships, the dangers and the collisions of personalities.

Positioned at floor level, In front of you so to speak, 1985 by Aston Ernest by Ryan Gander, 2011 is a slide presentation onto the wall of the space. The full carousel contains 40 slides of black and white images of the London Underground map junctions and dissections of text from a poem written by the fictional artist Aston Ernest about an artwork by the deceased artist Vivi Enkyo, entitled Blood Fountain, 1983. The artwork in recent years has mistakenly been seen as a sort of tribute to the life and works of the deceased artist Vivi Enkyo, as the work was in fact made as part of a number of works that constituted a collaborative body of work entitled A Physical Discussion, 1982, which took the form a game of sculptural ping pong whereby the two artists would respond to each other’s previous work by producing a new work and having it shipped to the other’s studio on completion. This work was previously shown at the Artangel project by Ryan Gander in London.

We never had a lot of $ around here, 2010 is a newly invented 25 US dollar coin (a quarter dollar) by Ryan Gander, envisaged as if fallen from 2027, the amount of which in relation to denomination is taken from a predicted average US area inflation rate. The coin is value side up and is glued to the floor. The first apparition of this work was at Intervals, a project by Ryan Gander at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Gander’s coins from the future explicitly raises the question of future value. Although almost everyone thinks about money and the future on a daily basis, rarely have artists intelligently addressed this issue, a further surprise given that contemporary art is no stranger to commodification.

Tell my mother not to worry (I), 2012 represents a white sheet thrown over the artist’s daughter, Olive. Ryan Gander imagines her as though she is walking through his studio, a tiny presence, omnipresent in his consciousness and spectre to the audience. The sculpture marks the first of a series of works that will follow Olive’s growth over time. The artist plays with the idea of traditional sculpture with the draping marble, while also inserting part of his intimate sphere, hidden but revealed.

Placed on the ground, Lost in my own recursive narrative, 2012 is another small-format slide show of 81 images of the artist directing two actresses in a photographer’s studio. The room is filled with crumpled backdrop paper and dry ice, in a partial reconstruction of the scene featuring Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills in Antonioni’s film, Blow Up. The two young ladies, overexcited and bare-chested, are having fun and destroying the photographer’s equipment, creating a chaos from which rises freedom—the rebellion of models against the dictatorship of images. The succession of images creates a feeling of suspended time, like pauses to a nonchalant game.

In the last exhibition room, a digital video transferred from a 16 mm film titled Man on a bridge – (a study of David Lange), 2008 shows a number of slightly differing takes of the same short sequence: A man walks over a bridge and seems to notice something over the railing on his left-hand side. As he moves in for a closer inspection, the film cuts, and is then followed by another take of the same shot.

This work features one of Gander’s fictional characters, David Lange. The scenario is simple: as a man crosses a bridge something just outside the camera frame catches his eye. He walks to the bridge parapet to peer over and, presumably, get a closer look. The film cuts and the same action is repeated. Ryan Gander asked actor Roger Lloyd-Pack to play the part of Lange. Lloyd-Pack – a stalwart British actor famous for his hangdog expression as the character Trigger in the BBC television comedy series and for playing the role of Sherlock Holmes more times than anyone else – performs the action an astonishing 50 times, each with a slight variation of body language. Each of these interpretations could also be read as an out-take from the cutting-room floor, suggesting that somewhere there is a perfect take – or that perhaps there is no such thing as a ‘right’ version. Both the repetition of the gesture and the insistence on the motive makes the public aware of the goal of this film, as what provokes the attention of the actor is always aside, inaccessible to the viewer. Man on a Bridge may seem reliant on symbolism – the potential of a bridge as a transition or link which essentially function on a structural level, in that their variation or multiplicity is itself an ode to possibility.

The exhibition Lost in my own recursive narrative engages with constant tension, between biographical, narrative and conceptual elements. From within the exhibition display itself, like a magician, Ryan Gander makes up new mechanisms and creates a perpetual movement into which the spectator can slide.

All images Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli

© Danilo Donzelli